Introduction to LLVM - Compiling JavaScript to LLVM (Rust:inkwell) JIT

I, who had no knowledge of LLVM, a compiler infrastructure, have managed to parse JavaScript source code and compile it with LLVM.

There are many articles about LLVM, but I felt there were few for beginners, so in this article, I will try to write an article that can introduce LLVM as simply as possible.

The source code is placed here.

https://github.com/silverbirder/rustscript

Self-introduction

I am an engineer who usually uses interpreted languages such as JavaScript and Python. I was a person who had no knowledge of LLVM.

Background

In the past, I tried to create a toy browser. (Learning the mechanism of browsers) I was able to understand the basic operations by writing a part that parses HTML and CSS and renders it. If it's HTML and CSS, I thought the next would be JS, so I wanted to write a JS execution engine. However, the part where the web browser's API and JS execution engine are bound (EX.DOM operation) is difficult, so First of all, I thought I would create something that can process simple operations, arithmetic operations, and fizzbuzz.

What is a compiler?

A compiler is,

compiler is a computer program that translates computer code written in one programming language (the source language) into another language (the target language). The name "compiler" is primarily used for programs that translate source code from a high-level programming language to a lower level language (e.g. assembly language, object code, or machine code) to create an executable program.

※ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compiler

As written, a compiler refers to a program that converts one code into another code. It is mainly used in the sense of converting from a high-level language (ex. javascript) to a low-level language (ex. assembly language).

Compiling a program is mainly processed in the following order.

- Source code

- Lexical analysis

- Syntax analysis

- Syntax tree

- Intermediate language

- Code generation

Lexical analysis ~ Syntax tree, I think the software called lex and yacc is famous. This time, I will use something called swc_ecma_parser. swc_ecma_parser is a parser used in swc.

EcmaScript/TypeScript parser for the rust programming language. Passes almost all tests from tc39/test262.

It seems to pass most of the test cases of tc39/test262. tc39/test262 is a test suite that guarantees the following specification behaviors.

ECMA-262, ECMAScript Language Specification

ECMA-402, ECMAScript Internationalization API Specification

ECMA-404, The JSON Data Interchange Format (pdf)

The actual test code is located at tc39/test262/test.

I was considering whether to create the parser part myself. If I were to create it myself, I would have to follow these steps:

- Understanding the language grammar

- Implementing the parsing process

- Automatic parsing generation from BNF or PEG is also possible

To know about the language grammar in ①, I was looking for the BNF of ecmascript. Then, as far as I researched, I arrived at the following page.

https://tc39.es/ecma262/#sec-grammar-summary

This was the test suite target of the earlier swc_ecma_parser, tc39/test262/test, so I didn't feel like rebuilding it and gave up on creating it myself.

For intermediate language ~ code generation, I'm thinking of using a compilation infrastructure called LLVM.

What is LLVM

According to the official page, LLVM is

The LLVM Project is a collection of modular and reusable compiler and toolchain technologies.

The LLVM project is a general term for highly reusable compiler and toolchain technologies. LLVM has the following features:

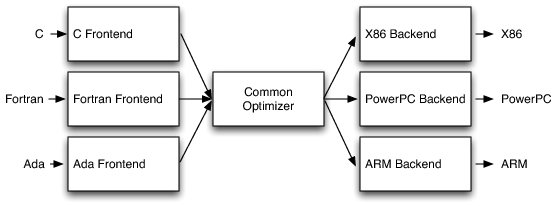

LLVM is a set of compiler and toolchain technologies, which can be used to develop a front end for any programming language and a back end for any instruction set architecture. LLVM is designed around a language-independent intermediate representation (IR) that serves as a portable, high-level assembly language that can be optimized with a variety of transformations over multiple passes.

※ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LLVM

LLVM can convert from any front-end language (the language before conversion in the context of a compiler) to any instruction set architecture (ISA) backend. It is also designed around a language-independent intermediate language (IR).

Instruction set architecture means the following:

An instruction set is a system of instruction words for operating a certain microprocessor (CPU/MPU). It is a specification of machine language (machine language) that the processor can interpret and execute directly.

※ https://e-words.jp/w/CommandSet.html

The instructions to operate the processor are, for example, Load(LDR) and Store(STR). Load sets from memory to register, and Store is the opposite. A list is available in the Instruction(Builder) to be introduced later.

This time, the front-end language of LLVM is, as the title suggests, written in Rust. I just wanted to try it in Rust. As an LLVM library, we use inkwell. This is a thin wrapper library that allows you to use LLVM's C API safely.

The backend of LLVM will be run on a local machine.

Specifically, it will be x86_64-apple-darwin20.6.0.

I haven't tried it, but it seems that WASM can also be selected as a backend. This is a past article (LLVM 8.0, which officially supports WebAssembly, has been released - Publickey), but LLVM has supported WebAssembly (hereinafter, WASM) as a backend.

By the way, WASM is designed as a virtual ISA.

WebAssembly, or "wasm", is a general-purpose virtual ISA designed to be a compilation target for a wide variety of programming languages.

Things to know in LLVM development

In LLVM, you generate IR.

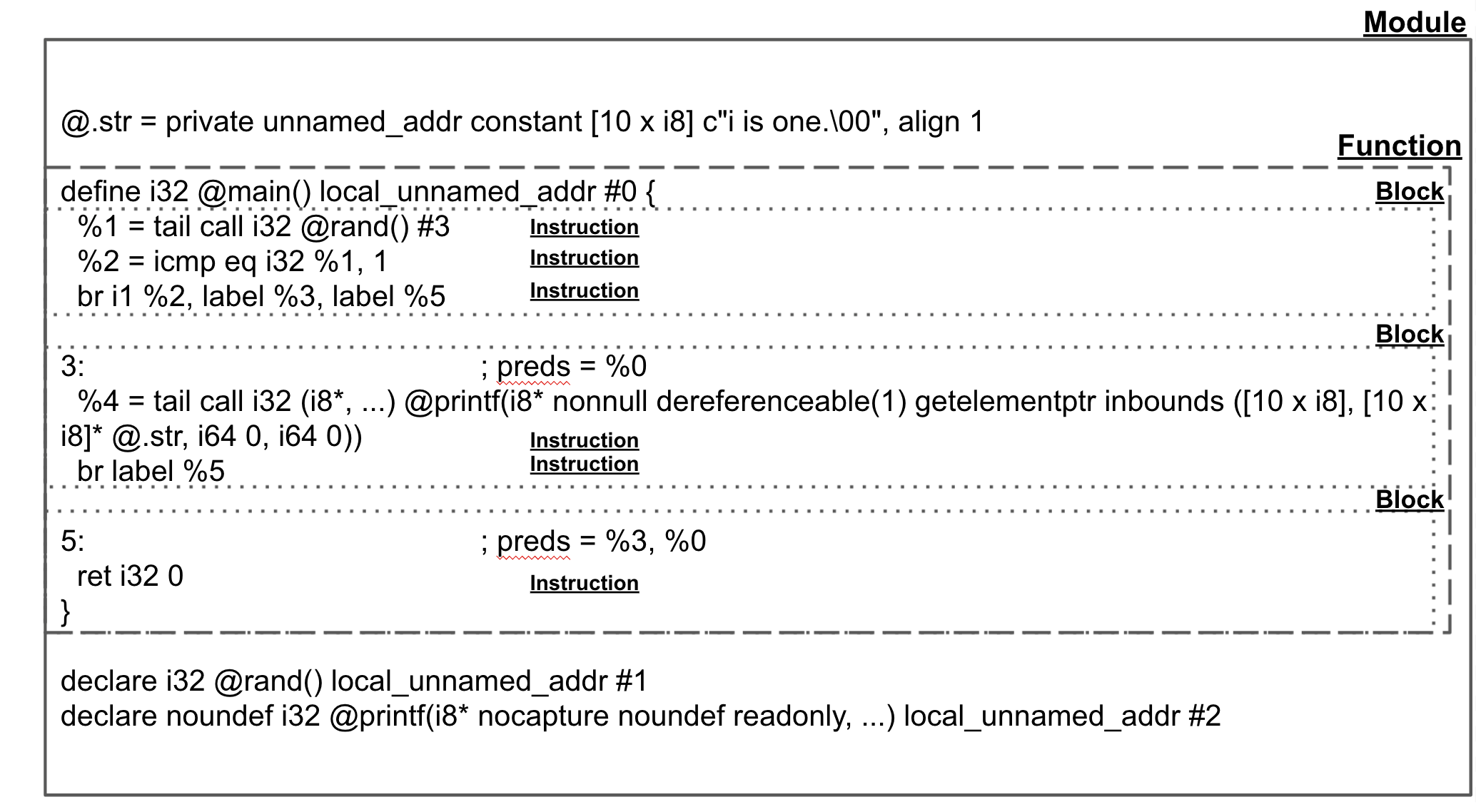

In that IR, it is structured as Module ⊇ Function ⊇ Block ⊇ Instruction(Builder).

If you don't know this, it's hard to understand LLVM code. (You may misunderstand it by interpreting it in your own words)

I will show an example with a small C language code and IR. I chose C, not Rust, because it's easy to output IR from clang.

// if.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(void)

{

int i = rand();

if (i == 1)

{

printf("i is one.");

}

return 0;

}

Convert this to IR

$ clang -S -emit-llvm -O3 if.c

The output file is an IR file called if.ll.

From there, look at the @main code.

@.str = private unnamed_addr constant [10 x i8] c"i is one.\00", align 1

define i32 @main() local_unnamed_addr #0 {

%1 = tail call i32 @rand() #3

%2 = icmp eq i32 %1, 1

br i1 %2, label %3, label %5

3: ; preds = %0

%4 = tail call i32 (i8*, ...) @printf(i8* nonnull dereferenceable(1) getelementptr inbounds ([10 x i8], [10 x i8]* @.str, i64 0, i64 0))

br label %5

5: ; preds = %3, %0

ret i32 0

}

declare i32 @rand() local_unnamed_addr #1

declare noundef i32 @printf(i8* nocapture noundef readonly, ...) local_unnamed_addr #2

If you divide the IR into Module, Function, Block, Instruction, it looks like the following image.

I will briefly explain what each one is.

Module

LLVM programs are composed of Module’s, each of which is a translation unit of the input programs.

※ https://llvm.org/docs/LangRef.html#module-structure

Modules serve as the units of conversion for the input program. Modules contain functions, global variables, and symbol table entries.

Function

LLVM function definitions consist of the “define” keyword. A function definition contains a list of basic blocks.

※ https://llvm.org/docs/LangRef.html#functions

A function contains multiple blocks (Block).

Block

Each basic block may optionally start with a label (giving the basic block a symbol table entry), contains a list of instructions, and ends with a terminator instruction (such as a branch or function return).

※ https://llvm.org/docs/LangRef.html#functions

A block starts with a label and contains multiple instructions (Instruction).

Instruction

The LLVM instruction set consists of several different classifications of instructions: terminator instructions, binary instructions, bitwise binary instructions, memory instructions, and other instructions.

※ https://llvm.org/docs/LangRef.html#instruction-reference

Instructions include various types such as binary instructions and memory instructions.

Reference Materials

The following materials are useful for reference.

- Tutorials

- C++ Kaleidoscope

- Rust Kaleidoscope

- The codegen does not work, so it can only be used up to a certain point

- Rust + inkwell Kaleidoscope

- LLVM References

Let's Try LLVM

After a long introduction, I would like to actually try LLVM.

Development Environment

Here is my environment (Mac).

$ sw_vers

ProductName: macOS

ProductVersion: 11.6

BuildVersion: 20G165

$ cargo --version && rustc --version

cargo 1.56.0-nightly (18751dd3f 2021-09-01)

rustc 1.56.0-nightly (50171c310 2021-09-01)

To install llvm, as a Mac user, I will install llvm from brew. It seems you can also download from the official page.

Once the installation is complete, you can use tools such as clang and llc.

$ clang --version

Homebrew clang version 13.0.0

Target: x86_64-apple-darwin20.6.0

Thread model: posix

InstalledDir: /usr/local/opt/llvm/bin

$ llc -version

Homebrew LLVM version 12.0.1

It seems that clang is included in Xcode on Mac. There is no problem using this. (However, the clang in xcode does not support wasm)

# xcode付属のclangの場合

$ clang --version

Apple clang version 12.0.5 (clang-1205.0.22.9)

Target: x86_64-apple-darwin20.6.0

Thread model: posix

InstalledDir: /Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/Developer/Toolchains/XcodeDefault.xctoolchain/usr/bin

The dependencies in Cargo.toml are as follows.

[dependencies]

inkwell = { git = "https://github.com/TheDan64/inkwell", branch = "master", features = ["llvm12-0"] }

swc_ecma_parser = "0.73.0"

swc_common = { version = "0.13.0", features=["tty-emitter"] }

swc_ecma_ast = "0.54.0"

Outputting "Hello World"

First, let's output Hello World. The Rust code is as follows.

extern crate inkwell;

use inkwell::context::Context;

use inkwell::OptimizationLevel;

fn main() {

let context = Context::create();

let i32_type = context.i32_type();

let i8_type = context.i8_type();

let i8_ptr_type = i8_type.ptr_type(inkwell::AddressSpace::Generic);

// Module

let module = context.create_module("main");

// Function

let printf_fn_type = i32_type.fn_type(&[i8_ptr_type.into()], true);

let printf_function = module.add_function("printf", printf_fn_type, None);

let main_fn_type = i32_type.fn_type(&[], false);

let main_function = module.add_function("main", main_fn_type, None);

// Block

let entry_basic_block = context.append_basic_block(main_function, "entry");

// Instruction(Builder)

let builder = context.create_builder();

builder.position_at_end(entry_basic_block);

let hw_string_ptr = builder.build_global_string_ptr("Hello, world!\n", "hw");

builder.build_call(printf_function, &[hw_string_ptr.as_pointer_value().into()], "call");

builder.build_return(Some(&i32_type.const_int(0, false)));

let execution_engine = module.create_jit_execution_engine(OptimizationLevel::Aggressive).unwrap();

unsafe {

execution_engine.get_function::<unsafe extern "C" fn()>("main").unwrap().call();

}

}

Let's run it.

$ cargo run

Hello, world!

It was able to run with LLVM's JIT compiler.

By the way, if you want to check what the IR is like, use module.print_to_file.

When you actually output it, the result is as follows.

; ModuleID = 'main'

source_filename = "main"

@hw = private unnamed_addr constant [15 x i8] c"Hello, world!\0A\00", align 1

declare i32 @printf(i8*, ...)

define i32 @main() {

entry:

%call = call i32 (i8*, ...) @printf(i8* getelementptr inbounds ([15 x i8], [15 x i8]* @hw, i32 0, i32 0))

ret i32 0

}

Rust's execution_engine.get_function::<unsafe extern "C" fn()>("main").unwrap().call(); is executing the IR's @main function.

The @main function is executing the @printf function, which is the printf in C language.

For research on IR code, the LLVM Language Reference Manual is invaluable.

It's interesting to investigate getelementptr.

SUM

Next, let's create a SUM function that takes three numbers as arguments and returns the result of adding them. The Rust code is as follows.

extern crate inkwell;

use inkwell::OptimizationLevel;

use inkwell::context::Context;

use std::error::Error;

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let context = Context::create();

let i64_type = context.i64_type();

let fn_type = i64_type.fn_type(&[i64_type.into(), i64_type.into(), i64_type.into()], false);

// Module

let module = context.create_module("main");

let builder = context.create_builder();

// Function

let function = module.add_function("sum", fn_type, None);

// Block

let basic_block = context.append_basic_block(function, "entry");

// Instruction(Builder)

builder.position_at_end(basic_block);

let x = function.get_nth_param(0).unwrap().into_int_value();

let y = function.get_nth_param(1).unwrap().into_int_value();

let z = function.get_nth_param(2).unwrap().into_int_value();

let sum = builder.build_int_add(x, y, "sum");

let sum = builder.build_int_add(z, sum, "sum");

builder.build_return(Some(&sum));

let execution_engine = module.create_jit_execution_engine(OptimizationLevel::None)?;

unsafe {

let x = 1u64;

let y = 2u64;

let z = 3u64;

let r = execution_engine.get_function::<unsafe extern "C" fn(u64, u64, u64)-> u64>("sum")?.call(x, y , z);

println!("{:?}", r);

};

Ok(())

}

Let's run it.

$ cargo run

6

Successfully, we were able to add 1 + 2 + 3.

By the way, I will also output the IR.

; ModuleID = 'main'

source_filename = "main"

target datalayout = "e-m:o-p270:32:32-p271:32:32-p272:64:64-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128"

define i64 @sum(i64 %0, i64 %1, i64 %2) {

entry:

%sum = add i64 %0, %1

%sum1 = add i64 %2, %sum

ret i64 %sum1

}

As before, Rust's execution_engine.get_function::<unsafe extern "C" fn(u64, u64, u64)-> u64>("sum")?.call(x, y , z); corresponds to the IR's @sum function.

We were able to use the Instruction for addition.

FizzBuzz

Next, let's do FizzBuzz. We will use new division and if commands. The Rust code is as follows.

extern crate inkwell;

use inkwell::context::Context;

use inkwell::IntPredicate::EQ;

use inkwell::OptimizationLevel;

use std::error::Error;

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let context = Context::create();

let i64_type = context.i64_type();

let void_type = context.void_type();

let i8_type = context.i8_type();

let i8_ptr_type = i8_type.ptr_type(inkwell::AddressSpace::Generic);

let fn_type = i64_type.fn_type(&[i64_type.into()], false);

let null = i8_ptr_type.const_null();

// Module

let module = context.create_module("fizz_buzz");

// Function

let printf_fn_type = void_type.fn_type(&[i8_ptr_type.into()], true);

let printf_function = module.add_function("printf", printf_fn_type, None);

let fizz_buzz_function = module.add_function("fizz_buzz", fn_type, None);

// Block

let block = context.append_basic_block(fizz_buzz_function, "entry");

// Instruction

let builder = context.create_builder();

builder.position_at_end(block);

let fizz_buzz_string_ptr = builder.build_global_string_ptr("FizzBuzz\n", "fizz_buzz");

let fizz_string_ptr = builder.build_global_string_ptr("Fizz\n", "fizz");

let buzz_string_ptr = builder.build_global_string_ptr("Buzz\n", "buzz");

let param_0 = fizz_buzz_function

.get_nth_param(0)

.unwrap()

.into_int_value();

let rem_divied_by_3 =

builder.build_int_signed_rem(param_0, i64_type.const_int(3, false), "rem_3");

let rem_divied_by5 =

builder.build_int_signed_rem(param_0, i64_type.const_int(5, false), "rem_5");

let rem_divied_by15 =

builder.build_int_signed_rem(param_0, i64_type.const_int(15, false), "rem_15");

let comp_that_is_divisible_by_3 = builder.build_int_compare(

EQ,

rem_divied_by_3,

i64_type.const_int(0, false),

"if_can_divide_by_3",

);

let comp_that_is_divisible_by_5 = builder.build_int_compare(

EQ,

rem_divied_by5,

i64_type.const_int(0, false),

"if_can_divide_by_5",

);

let comp_that_is_divisible_by_15 = builder.build_int_compare(

EQ,

rem_divied_by15,

i64_type.const_int(0, false),

"if_can_divide_by_15",

);

// Block

let fizz_buzz_block = context.append_basic_block(fizz_buzz_function, "fizz_buzz");

let fizz_block = context.append_basic_block(fizz_buzz_function, "fizz");

let buzz_block = context.append_basic_block(fizz_buzz_function, "buzz");

let num_block = context.append_basic_block(fizz_buzz_function, "num");

let else_1_block = context.append_basic_block(fizz_buzz_function, "else_1");

let else_2_block = context.append_basic_block(fizz_buzz_function, "else_2");

let end_block = context.append_basic_block(fizz_buzz_function, "end_block");

// Instruction

builder.build_conditional_branch(comp_that_is_divisible_by_15, fizz_buzz_block, else_1_block);

builder.position_at_end(fizz_buzz_block);

builder.build_call(

printf_function,

&[fizz_buzz_string_ptr.as_pointer_value().into()],

"print_fizz_buzz",

);

builder.build_unconditional_branch(end_block);

// Instruction

builder.position_at_end(else_1_block);

builder.build_conditional_branch(comp_that_is_divisible_by_3, fizz_block, else_2_block);

builder.position_at_end(fizz_block);

builder.build_call(

printf_function,

&[fizz_string_ptr.as_pointer_value().into()],

"print_fizz",

);

builder.build_unconditional_branch(end_block);

// Instruction

builder.position_at_end(else_2_block);

builder.build_conditional_branch(comp_that_is_divisible_by_5, buzz_block, num_block);

builder.position_at_end(buzz_block);

builder.build_call(

printf_function,

&[buzz_string_ptr.as_pointer_value().into()],

"print_buzz",

);

builder.build_unconditional_branch(end_block);

// Instruction

builder.position_at_end(num_block);

builder.build_call(

printf_function,

&[buzz_string_ptr.as_pointer_value().into()], // TODO: Print input num.

"print_num",

);

builder.build_unconditional_branch(end_block);

// Instruction

builder.position_at_end(end_block);

builder.build_return(Some(&null));

let e = module.create_jit_execution_engine(OptimizationLevel::None)?;

unsafe {

let x = 15u64;

e.get_function::<unsafe extern "C" fn(u64) -> ()>("fizz_buzz")?

.call(x);

}

Ok(())

}

In the if statement, it seems that build_conditional_branch and build_unconditional_branch are used.

It was written in inkwell/examples/kaleidoscope/main.rs, so I tried it.

Let's run it. We are calling with 15 as an argument.

$ cargo run

FizzBuzz

Success! By the way, I will also output the IR.

; ModuleID = 'fizz_buzz'

source_filename = "fizz_buzz"

@fizz_buzz.1 = private unnamed_addr constant [10 x i8] c"FizzBuzz\0A\00", align 1

@fizz = private unnamed_addr constant [6 x i8] c"Fizz\0A\00", align 1

@buzz = private unnamed_addr constant [6 x i8] c"Buzz\0A\00", align 1

declare void @printf(i8*, ...)

define i64 @fizz_buzz(i64 %0) {

entry:

%rem_3 = srem i64 %0, 3

%rem_5 = srem i64 %0, 5

%rem_15 = srem i64 %0, 15

%if_can_divide_by_3 = icmp eq i64 %rem_3, 0

%if_can_divide_by_5 = icmp eq i64 %rem_5, 0

%if_can_divide_by_15 = icmp eq i64 %rem_15, 0

br i1 %if_can_divide_by_15, label %fizz_buzz, label %else_1

fizz_buzz: ; preds = %entry

call void (i8*, ...) @printf(i8* getelementptr inbounds ([10 x i8], [10 x i8]* @fizz_buzz.1, i32 0, i32 0))

br label %end_block

fizz: ; preds = %else_1

call void (i8*, ...) @printf(i8* getelementptr inbounds ([6 x i8], [6 x i8]* @fizz, i32 0, i32 0))

br label %end_block

buzz: ; preds = %else_2

call void (i8*, ...) @printf(i8* getelementptr inbounds ([6 x i8], [6 x i8]* @buzz, i32 0, i32 0))

br label %end_block

num: ; preds = %else_2

call void (i8*, ...) @printf(i8* getelementptr inbounds ([6 x i8], [6 x i8]* @buzz, i32 0, i32 0))

br label %end_block

else_1: ; preds = %entry

br i1 %if_can_divide_by_3, label %fizz, label %else_2

else_2: ; preds = %else_1

br i1 %if_can_divide_by_5, label %buzz, label %num

end_block: ; preds = %num, %buzz, %fizz, %fizz_buzz

ret i8* null

}

The number of Blocks has increased dramatically. That's because there are many if, else in FizzBuzz.

I'm starting to gain some confidence in LLVM.

So far, we have done intermediate language ~ code generation with LLVM.

Let's go back a bit and do the lexical analysis ~ syntax tree part, in other words, the parsing process.

Parsing Javascript that Performs Arithmetic Operations

Let's parse javascript. We will use swc_ecma_parser. The javascript to parse is as follows.

// ./src/test.js

20 / 10;

The Rust code is as follows.

#[macro_use]

extern crate swc_common;

extern crate swc_ecma_ast;

extern crate swc_ecma_parser;

use std::path::Path;

use swc_common::sync::Lrc;

use swc_common::{

errors::{ColorConfig, Handler},

SourceMap,

};

use swc_ecma_parser::{lexer::Lexer, Parser, StringInput, Syntax};

fn main() {

let cm: Lrc<SourceMap> = Default::default();

let handler = Handler::with_tty_emitter(ColorConfig::Auto, true, false, Some(cm.clone()));

let fm = cm

.load_file(Path::new("./src/test.js"))

.expect("failed to load test.js");

let lexer = Lexer::new(

Syntax::Es(Default::default()),

// JscTarget defaults to es5

Default::default(),

StringInput::from(&*fm),

None,

);

let mut parser = Parser::new_from(lexer);

for e in parser.take_errors() {

e.into_diagnostic(&handler).emit();

}

let _module = parser

.parse_module()

.map_err(|mut e| e.into_diagnostic(&handler).emit())

.expect("failed to parser module");

println!("{:?}", _module);

}

Let's run it.

$ cargo run

Module { span: Span { lo: BytePos(0), hi: BytePos(8), ctxt: #0 }, body: [Stmt(Expr(ExprStmt { span: Span { lo: BytePos(0), hi: BytePos(8), ctxt: #0 }, expr: Bin(BinExpr { span: Span { lo: BytePos(0), hi: BytePos(7), ctxt: #0 }, op: "/", left: Lit(Num(Number { span: Span { lo: BytePos(0), hi: BytePos(2), ctxt: #0 }, value: 20.0 })), right: Lit(Num(Number { span: Span { lo: BytePos(5), hi: BytePos(7), ctxt: #0 }, value: 10.0 })) }) }))], shebang: None }

You've got a plausible result (20.0 or 10.0)!

Running Arithmetic Operations in Javascript with LLVM

Finally, let's combine swc_ecma_parser and LLVM to connect lexical analysis ~ syntax tree and intermediate language ~ code generation, parse arithmetic operation JS, and run it with LLVM.

The javascript to parse is as follows:

// ./src/test.js

20 / 10;

The Rust code is as follows:

extern crate inkwell;

extern crate swc_common;

extern crate swc_ecma_ast;

extern crate swc_ecma_parser;

use inkwell::context::Context;

use inkwell::OptimizationLevel;

use std::error::Error;

use std::path::Path;

use swc_common::sync::Lrc;

use swc_common::{

errors::{ColorConfig, Handler},

SourceMap,

};

use swc_ecma_ast::Lit::Num;

use swc_ecma_parser::{lexer::Lexer, Parser, StringInput, Syntax};

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let cm: Lrc<SourceMap> = Default::default();

let handler = Handler::with_tty_emitter(ColorConfig::Auto, true, false, Some(cm.clone()));

let fm = cm

.load_file(Path::new("./src/test.js"))

.expect("failed to load test.js");

let lexer = Lexer::new(

Syntax::Es(Default::default()),

Default::default(),

StringInput::from(&*fm),

None,

);

let mut parser = Parser::new_from(lexer);

for e in parser.take_errors() {

e.into_diagnostic(&handler).emit();

}

let _module = parser

.parse_module()

.map_err(|e| e.into_diagnostic(&handler).emit())

.expect("failed to parser module");

let context = Context::create();

let module = context.create_module("main");

let builder = context.create_builder();

for b in _module.body {

if b.is_stmt() {

let stmt = b.stmt().unwrap();

if stmt.is_expr() {

let expr_stmt = stmt.expr().unwrap();

let expr = expr_stmt.expr;

if expr.is_bin() {

let bin_expr = expr.bin().unwrap();

let left_expr = bin_expr.left;

let right_expr = bin_expr.right;

let binary_op = bin_expr.op;

if left_expr.is_lit() && right_expr.is_lit() {

let left_lit = left_expr.lit().unwrap();

let right_lit = right_expr.lit().unwrap();

let left_value = match left_lit {

Num(n) => n.value,

_ => 0f64,

};

let right_value = match right_lit {

Num(n) => n.value,

_ => 0f64,

};

let i64_type = context.i64_type();

let void_type = context.void_type();

let fn_type = void_type.fn_type(&[], false);

let function = module.add_function("main", fn_type, None);

let basic_block = context.append_basic_block(function, "entry");

builder.position_at_end(basic_block);

let x = i64_type.const_int(left_value as u64, true);

let y = i64_type.const_int(right_value as u64, true);

let result = match binary_op {

swc_ecma_ast::BinaryOp::Add => builder.build_int_add(x, y, "main"),

swc_ecma_ast::BinaryOp::Sub => builder.build_int_sub(x, y, "main"),

swc_ecma_ast::BinaryOp::Div => {

builder.build_int_signed_div(x, y, "main")

}

swc_ecma_ast::BinaryOp::Mul => builder.build_int_mul(x, y, "main"),

_ => i64_type.const_int(0u64, true),

};

builder.build_return(Some(&result));

let e = module.create_jit_execution_engine(OptimizationLevel::None)?;

unsafe {

let r = e

.get_function::<unsafe extern "C" fn() -> u64>("main")?

.call();

println!("{:?}", r);

}

}

}

}

}

}

Ok(())

}

Let's run it.

$ cargo run

2

20 / 10, in other words, 2 was output! We did it!

In Conclusion

With this, we've managed to parse simple javascript code and run it with LLVM. Initially, I had no idea how to use LLVM, but as I gradually increased what I could do, my understanding and motivation increased. If you're studying LLVM, please use this as a reference.

Share

Related tags

- Getting Started with Feature Flags in Unleash

- Automating Synchronization with GitHub Actions and Pull Requests

- The GraphQL Guild Ecosystem is Convenient, Isn't It?

- Crawlee is Handy for Quick Crawling

- Self-hosting a Cache Server with turborepo-remote-cache

- Trying Data Transformation with urql

- How to display Twitter embedded content in an iframe after rendering

- Mockable unit testing methodology completed only with BigQuery

- Memo Micro Frontends

- Want to be a Virtual Beauty on Mac! (Zoom + Gachikoe + 3Tene or Reality)